| The College Dropout | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Studio album by | |||

| Released | February 10, 2004 | ||

| Recorded | 1999–2003 | ||

| Studio |

| ||

| Genre | Hip hop | ||

| Length | 76:13 | ||

| Label | |||

| Producer |

| ||

| Kanye West chronology | |||

| |||

| Singles from The College Dropout | |||

| |||

Download Kanye West - The College Dropout (2004) torrent or any other torrent from category. Direct download via HTTP available as well. Kanye West - The College Dropout 9 torrent download locations thepiratebay.se Kanye West - The College Dropout @320 Audio Music 13 days monova.org Kanye West - The College Dropout Other 19 hours idope.se Kanye West - The College Dropout music 4 months seedpeer.eu Kanye West - The College Dropout @320 Music Misc 21 hours.

The College Dropout is the debut studio album by American rapper and producer Kanye West. It was released on February 10, 2004, by Def Jam Recordings and Roc-A-Fella Records.

In the years leading up to the album, West had received praise for his production work for rappers such as Jay-Z and Talib Kweli, but faced difficulty being accepted as an artist in his own right by figures in the music industry. Intent on pursuing a solo career, he signed a record deal with Roc-A-Fella and recorded The College Dropout over a period of four years, beginning in 1999.

The album's production was primarily handled by West and developed his 'chipmunk soul' production style, which made use of sped-up, pitch shifted vocal samples from soul and R&B records, in addition to West's own drum programming, string accompaniments, and gospel choirs; it also features contributions from Jay-Z, Mos Def, Jamie Foxx, Syleena Johnson, and Ludacris, among others. Diverging from the then-dominant gangster persona in hip hop, West's lyrics concern themes of family, self-consciousness, materialism, religion, racism, and higher education.

The College Dropout debuted at number two on the US Billboard 200, selling 441,000 copies in its first week of sales. It was a massive commercial success, becoming West's best-selling album in the United States, with domestic sales of over 3.4 million copies by 2014. The album was promoted with singles such as 'Through the Wire', 'Jesus Walks', 'All Falls Down', and 'Slow Jamz', the latter two of which peaked within the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100.

A widespread critical success, The College Dropout was praised for West's production, humorous and emotional raps, and the music's balance of self-examination and mainstream sensibilities. It earned the rapper several accolades including a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album at the 47th Annual Grammy Awards. It has since been named by Time, Rolling Stone, and other publications as one of the greatest albums of all time.

- 6Critical reception

- 7Track listing

- 8Personnel

- 9Charts

Background[edit]

Kanye West began his early production career in the mid-1990s, making beats primarily for burgeoning local artists, eventually developing a style that involved speeding up vocal samples from classic soul records. For a time, he acted as a ghost producer for Deric 'D-Dot' Angelettie. Due to his association with D-Dot, West wasn't able to release a solo album, so he formed and became a member and producer of the Go-Getters, a late-1990s Chicago rap group composed of him, GLC, Timmy G, Really Doe, and Arrowstar.[1][2] The group released their first and only studio album World Record Holders in 1999.[1] West came to achieve recognition and is often credited with revitalizing Jay-Z's career with his contributions to the rap mogul's influential 2001 album The Blueprint.[3]The Blueprint has been named by Rolling Stone as the 252nd greatest album of all time and the critical and financial success of the album generated substantial interest in West as a producer.[4] Serving as an in-house producer for Roc-A-Fella Records, West produced records for other artists from the label, including Beanie Sigel, Freeway, and Cam'ron. He also crafted hit songs for Ludacris, Alicia Keys, and Janet Jackson.[3][5][6][7]

Although he had attained success as a producer, Kanye West aspired to be a rapper, but had struggled to attain a record deal.[6] Record companies ignored him because he did not portray the gangsta image prominent in mainstream hip hop at the time.[8] After a series of meetings with Capitol Records, West was ultimately denied an artist deal.[9] According to Capitol Record's A&R, Joe Weinberger, he was approached by West and almost signed a deal with him, but another person in the company convinced Capitol's president not to.[9] Desperate to keep West from defecting to another label, then-label head Damon Dash reluctantly signed West to Roc-A-Fella Records. Jay-Z, West's colleague, later admitted that Roc-A-Fella was initially reluctant to support West as a rapper, claiming that many saw him as a producer first and foremost, and that his background contrasted with that of his labelmates.[8][10]

West's breakthrough came a year later on October 23, 2002, when, while driving home from a California recording studio after working late, he fell asleep at the wheel and was involved in a near-fatal car crash.[11] The crash left him with a shattered jaw, which had to be wired shut in reconstructive surgery. The accident inspired West; two weeks after being admitted to a hospital, he recorded a song at the Record Plant with his jaw still wired shut.[11] The composition, 'Through the Wire', expressed West's experience after the accident, and helped lay the foundation for his debut album, as according to West 'all the better artists have expressed what they were going through'.[12][13] West added that 'the album was my medicine', as working on the record distracted him from the pain.[14] 'Through the Wire' was first available on West's Get Well Soon...mixtape, released December 2002.[15] At the same time, West announced that he was working on an album called The College Dropout, whose overall theme was to 'make your own decisions. Don't let society tell you, 'This is what you have to do.'[16]

Recording[edit]

West began recording The College Dropout in 1999, taking four years to complete.[17] Recording sessions took place at Record Plant in Los Angeles, California, but the production featured on the record took place elsewhere over the course of several years. According to John Monopoly, West's friend, manager and business partner, the album '...[didn't have] a particular start date. He's been gathering beats for years. He was always producing with the intention of being a rapper. There's beats on the album he's been literally saving for himself for years.' At one point, West hovered between making a portion of the production in the studio and the majority within his own apartment in Newark, New Jersey. Because it was a two-bedroom apartment, West was able to set up a home studio in one of the rooms and his bedroom in the other.[6]

West brought with him to the studio a Louis Vuitton backpack filled with old disks and demos to the studio, producing tracks in less than fifteen minutes at a time. He recorded the remainder of the album in Los Angeles while recovering from the car accident. Once he had completed the album, it was leaked months before its release date.[6] However, West decided to use the opportunity to review the album, and The College Dropout was significantly remixed, remastered, and revised before being released. As a result, certain tracks originally destined for the album were subsequently retracted, among them 'Keep the Receipt' with Ol' Dirty Bastard and 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly' with Consequence.[18] West meticulously refined the production, adding string arrangements, gospel choirs, improved drum programming and new verses.[6] On his personal blog in 2009, West stated he was most inspired by The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and listened to the album everyday while working on The College Dropout.[19]

The song 'School Spirit' was censored for the album because Aretha Franklin would not allow the rapper to sample her music without censorship being promised.[20] It was revealed by Plain Pat that there were around three other versions of the song, but West disliked them. Pat said in reference to the Franklin sample: 'That song would have been so weak if we didn't get that sample cleared.'.[21] In 2011, an uncensored version of the track was distributed online.[22]

West finished recording around December 2003, according to his older cousin and singer Tony Williams, who was recruited by the rapper two weeks before the album's deadline to contribute vocals. Williams had impressed West by singing improvisations to 'Spaceship' during one of their drives together. The singer later recounted recording with West at the Record Plant: 'I get in, go in the booth, start vibing out on 'Spaceship' and finished it up. At that point he was like, 'Ok, Well let me see what you do on this song.' I think that's when we did 'Last Call.' One song lead to another, and by the end of the weekend, I was on like five songs. Then we did the 'I'll Fly Away' joint.'[23]

Music and lyrics[edit]

The College Dropout diverged from the then-dominant gangster persona in hip hop in favor of more diverse, topical subjects for the lyrics.[13] Throughout the album, West touches on a number of different issues drawn from his own experiences and observations, including organized religion, family, sexuality, excessive materialism, self-consciousness, minimum wage labor, institutional prejudice, and personal struggles.[24][25][26] Music journalist Kelefa Sanneh wrote, 'Throughout the album, Mr. West taunts everyone who didn't believe in him: teachers, record executives, police officers, even his former boss at the Gap'.[27] West explained, 'My persona is that I'm the regular person. Just think about whatever you've been through in the past week, and I have a song about that on my album.'[28] The album was musically notable for West's unique development of his 'chipmunk soul' production style,[29] in which R&B and soul musicsamples were sped up and pitch shifted.[30][31]

'Through the Wire' is an autobiographical song about West's 2002 car accident when he had to have his jaw wired shut. The track is representative of his production style, in which he samples and speeds up sections from classic soul records and uses them to create melodic hooks. | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The album begins with a skit featuring a college professor asking West to deliver a graduation speech. The skit is followed by 'We Don't Care' featuring West comically celebrating drug life with lines like 'We wasn't supposed to make it past 25, joke's on you, we still alive' and then criticizing its influence amongst children.[27] The next track, 'Graduation Day', features Miri Ben-Ari on violin,[32] and vocals by John Legend.[33]

On 'All Falls Down', West wages an attack on consumerism.[5][34] The song features singer Syleena Johnson and contains an interpolation of Lauryn Hill's 'Mystery of Iniquity'.[33] West called upon Johnson to re-sing a vocal portion of 'Mystery of Iniquity', which ended up in the final mix.[35] Gospel hymn with doo-wop elements 'I'll Fly Away' precedes 'Spaceship', a track with a relaxed beat containing a soulful Marvin Gaye sample. The lyrics are mostly critical of the working world, where West muses about flying away in a spaceship to leave his boring job, and guest rappers GLC and Consequence add comparisons to modern day retail environment with slavery.[34]

On 'Jesus Walks', West professes his belief in Jesus, while also discussing how religion is used by various people and how the media seems to avoid songs that address matters of faith while embracing compositions on violence, sex, and drugs.[34][36] 'Jesus Walks' is built around a sample of 'Walk With Me' as performed by the ARC Choir.[33] Garry Mulholland of The Observer described it as a 'towering inferno of martial beats, fathoms-deep chain gang backing chants, a defiant children's choir, gospel wails, and sizzling orchestral breaks.'[37] The first verse of the song is told through the eyes of a drug dealer seeking help from God, and it reportedly took over six months for West to draw inspiration for the second verse.[38]

'Never Let Me Down' is influenced by West's near-death car crash. The song features Jay-Z who rhymes about maintaining status and power given his chart success, with West commenting about racism and poverty.[34][39] The song features verses by spoken word performer J. Ivy who offers comments of upliftment. 'Never Let Me Down' reuses a Jay-Z verse first heard in the remix of his song 'Hovi Baby'.[34][40] 'Get Em High' is a collaboration by West with two socially conscious rappers, Talib Kweli and Common.[41] 'The New Workout Plan' is a call to fitness to improve one's love life.[34] 'Slow Jamz' features Twista and Jamie Foxx and serves as a tribute to classic smooth soul artists and slow jam songs.[5] The song also appeared on Twista's album Kamikaze.[5] On the song 'School Spirit', West relates the experience of dropping out of school and contains references to well-known fraternities, sororities, singer Norah Jones, and record label Roc-A-Fella Records. 'Two Words' features commentary on social issues and features Mos Def, Freeway, and the Harlem Boys Choir.[42]

'Through the Wire' features a high-pitched vocal sample of Chaka Khan and relates West's real life experience with being in a car accident.[11] The song provides a mostly comedic account of his difficult recovery, and features West rapping with his jaw still wired shut from the accident.[11][33] The chorus and instrumentals sample a pitched up version of Chaka Khan's 1985 single 'Through the Fire'.[5] 'Family Business' is a soulful tribute to the godbrother of Tarrey Torae, one of the many collaborators in the album.[43] The song 'Last Call' is about West's transition from being a producer to a rapper, and the album ends with a nearly nine-minute autobiographical monologue that follows the song 'Last Call', however, is not a separate track.[44]

Title and packaging[edit]

The album's title is in part a reference to West's decision to drop out of college to pursue his dream of becoming a musician.[45] This action greatly displeased his mother, who was a professor at the university from which he withdrew. She later said, 'It was drummed into my head that college is the ticket to a good life... but some career goals don't require college. For Kanye to make an album called College Dropout it was more about having the guts to embrace who you are, rather than following the path society has carved out for you.'[46]

The artwork for the album was developed by Eric Duvauchelle, who was then part of Roc-A-Fella's in-house brand design team. West had already taken pictures dressed as the Dropout Bear - which would reappear in his later work - and Duvauchelle picked the image of him sitting on a set of bleachers, as he was attracted to the loneliness of what was supposed to be 'the most popular representation of a school'. The image is framed inside gold ornaments, which Duvauchelle found in a book of illustrations from the 16th-century and West wanted to use to 'bring a sense of elegance and style to what was typically a gangster-led image of rap artists'. The inside cover follows a college yearbook, with photos of the featured artists of the albums from their youth.[47]

Release and promotion[edit]

The College Dropout was originally scheduled for release in August 2003, but West's perfectionist habits producing the album led to it being postponed three times. It was first delayed to October 2003, then to January 2004, before finally being released to stores on February 10, 2004.[48][49]

In its first week of release, the album sold 441,000 copies and debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 chart, behind Norah Jones' Feels Like Home.[50] It remained on the second spot behind Feels Like Home for two more weeks, with 196,000 units sold in the second week and 132,000 in the third week.[51][52] In April, it was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), indicating one million copies moved, and June 30 it was certified double Platinum.[53] By June 2014, The College Dropout had become West's best-selling album in the US, with domestic sales of 3,358,000 copies.[54][55] It has also sold over 4 million copies worldwide.[56] In 2004, The College Dropout was ranked as the twelfth most popular album of the year on the Billboard 200.[57]

Four of the singles released in promotion of the album became top-20 chart hits: 'Through the Wire', 'Slow Jamz', 'All Falls Down', and 'Jesus Walks'.[58] 'The New Workout Plan' was the fifth and last single.[59] 'Spaceship' was planned to be the sixth single, but Def Jam decided to move on from The College Dropout's promotional campaign to begin marketing West's next album, Late Registration.[60] At one point, 'Two Words' was also intended to be released as a single, and a video for the song was filmed, and later uploaded by West online in 2009.[41]

Critical reception[edit]

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 87/100[61] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [5] |

| Blender | [62] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[63] |

| Los Angeles Times | [64] |

| Mojo | [65] |

| Pitchfork | 8.2/10[3] |

| Rolling Stone | [66] |

| Spin | B+[67] |

| USA Today | [68] |

| The Village Voice | A[69] |

The College Dropout was met with widespread critical acclaim. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream publications, the album received an average score of 87, based on 25 reviews.[61]

The record was hailed by Kelefa Sanneh from The New York Times as '2004's first great hip-hop album'.[27] Reviewing it for The A.V. Club, Nathan Rabin observed in the music 'substance, social commentary, righteous anger, ornery humanism, dark humor, and even Christianity', calling it 'one of those wonderful crossover albums that appeal to a huge audience without sacrificing a shred of integrity'.[70]Mojo said its exceptional hip hop production was miraculous during a time when hip hop's practice of sampling was becoming 'increasingly litigious',[65] and URB deemed it 'both visceral and emotive, sprinkling the dancefloors with tears and sweat'.[71] Dave Heaton from PopMatters found it 'musically engaging' and 'a genuine extension of Kanye's personality and experiences',[34] while Hua Hsu of The Village Voice felt that his sped-up samples 'carry a humble, human air', allowing listeners to 'hear tiny traces of actual people inside'.[72] Fellow Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote that 'not only does [West] create a unique role model, that role model is dangerous—his arguments against education are as market-targeted as other rappers' arguments for thug life'.[69] In the opinion of Stylus Magazine's Josh Love, West 'subverts cliches from both sides of the hip-hop divide' while 'trying to reflect the entire spectrum of hip-hop and black experience, looking for solace and salvation in the traditional safehouses of church and family'.[24]Entertainment Weekly's Michael Endelman elaborated on West's avoidance of the then-dominant 'gangsta' persona of hip hop:

West delivers the goods with a disarming mix of confessional honesty and sarcastic humor, earnest idealism and big-pimping materialism. In a scene still dominated by authenticity battles and gangsta posturing, he's a middle-class, politically conscious, post-thug, bourgeois rapper – and that's nothing to be ashamed of.[63]

Some reviewers were more qualified in their praise. Rolling Stone's Jon Caramanica felt that 'West isn't quite MC enough to hold down the entire disc',[66] while Slant Magazine's Sal Cinquemani observed 'too many guest artists, too many interludes, and just too many songs period' on what he considered a 'chest-beatingly self-congratulatory' yet humorous, deeply sincere, and affecting record.[25] It was regarded by Pitchfork critic Rob Mitchum as a 'flawed, overlong, hypocritical, egotistical, and altogether terrific album'.[3]Rolling Stone was more receptive in a retrospective review, calling the album 'a demonstration that hip-hop—real, banging, commercial hip-hop—could be a vehicle for nuanced self-examination and musical subtlety.'[73]

Accolades[edit]

The College Dropout was voted as the best album of the year by Rolling Stone and in The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics.[74][75]Spin ranked it number one on its list of 40 Best Albums of the Year.[76] Comedian Chris Rock has attested to listening to The College Dropout while writing his material.[77] In 2005, Pitchfork named it No. 50 in their best albums of 2000–2004.[78] In 2006, the album was named by Time as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[79] In its retrospective 2007 issue, XXL awarded it a perfect 'XXL' rating, which had previously been given to only sixteen other albums.[80] In its July 4, 2008 issue, Entertainment Weekly listed College Dropout as the fourth best album of the past 25 years.[81] The magazine later listed it as the best album of the decade.[82]

Newsweek placed The College Dropout among its Best Albums of the Decade list at number three.[83]Rhapsody named it the seventh best album of the decade and the fourth best hip hop album of the decade.[84][85]Rolling Stone ranked it number 10 on its list of the 100 Best Albums of the Decade and stated, 'Kanye expanded the musical and emotional language of hip-hop ... he challenged all the rules, dancing across boundaries others were too afraid to even acknowledge'.[86]Consequence of Sound named it as the 16th best album of the decade.[87]Phoenix New Times named it the second best rap album of the decade.[88]Fact listed it as the 20th best album of the 2000s.[89] In 2012 Complex named the album one of the classic albums of the last decade,[90] and the 20th best hip hop debut album ever.[91] The same year Rolling Stone ranked The College Dropout number 298 on its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[92] and 19th on their list of debut records.[93] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[94]

Awards[edit]

| Year | Organization | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | American Music Awards | Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album | Nominated | [95] |

| Billboard Music Awards | R&B/Hip-Hop Album of the Year | Nominated | [96] | |

| MOBO Awards | Best Album | Won | [97] | |

| The Source Awards | Album of the Year | Won | [98] | |

| Teen Choice Awards | Album of the Year | Won | [99] | |

| 2005 | Grammy Awards | Album of the Year | Nominated | [100] |

| Best Rap Album | Won |

Track listing[edit]

- Information is adapted from the album's liner notes.[33]

- All tracks produced by Kanye West, except 'Last Call' (co-produced by Evidence; additional production by Porse) and 'Breathe in Breathe Out' (co-produced by Brian 'All Day' Miller).

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 'Intro (Skit)' | Kanye West | 0:19 |

| 2. | 'We Don't Care' | 3:59 | |

| 3. | 'Graduation Day' |

| 1:22 |

| 4. | 'All Falls Down' (featuring Syleena Johnson) | 3:43 | |

| 5. | 'I'll Fly Away' | Albert E. Brumley | 1:09 |

| 6. | 'Spaceship' (featuring GLC and Consequence) |

| 5:24 |

| 7. | 'Jesus Walks' | 3:13 | |

| 8. | 'Never Let Me Down' (featuring Jay-Z and J. Ivy) |

| 5:24 |

| 9. | 'Get Em High' (featuring Talib Kweli and Common) | 4:49 | |

| 10. | 'Workout Plan (Skit)' | West | 0:46 |

| 11. | 'The New Workout Plan' |

| 5:22 |

| 12. | 'Slow Jamz' (featuring Twista and Jamie Foxx) | 5:16 | |

| 13. | 'Breathe in Breathe Out' (featuring Ludacris) |

| 4:06 |

| 14. | 'School Spirit (Skit 1)' | West | 1:18 |

| 15. | 'School Spirit' | 3:02 | |

| 16. | 'School Spirit (Skit 2)' | West | 0:43 |

| 17. | 'Lil Jimmy (Skit)' | West | 0:53 |

| 18. | 'Two Words' (featuring Mos Def, Freeway and The Boys Choir of Harlem) |

| 4:26 |

| 19. | 'Through the Wire' | 3:41 | |

| 20. | 'Family Business' | West | 4:38 |

| 21. | 'Last Call' |

| 12:40 |

| Total length: | 76:13 | ||

2005 Japanese special edition[edit]

| Bonus track | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 22. | 'Heavy Hitters' (featuring GLC) | 3:01 | |

| Total length: | 80:08 | ||

| Bonus CD | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | 'We Don't Care (Reprise)' (featuring Keyshia Cole) | 2:57 |

| 2. | 'Jesus Walks (Remix)' (featuring Mase and Common) | 4:58 |

| 3. | 'It's Alright' (featuring Ma$e and John Legend) | 3:51 |

| 4. | 'The New Workout Plan (Remix)' (featuring Fonzworth Bentley, Luke and Twista; produced by Lil Jon) | 4:02 |

| 5. | 'Two Words (Cinematic)' (featuring The Harlem Boys Choir) | 4:06 |

| 6. | 'Never Let Me Down (Cinematic)' | 5:16 |

| Total length: | 25:07 | |

| Bonus DVD: The College Dropout Video Anthology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Director(s) | Length |

| 1. | 'Through the Wire' |

| 4:54 |

| 2. | 'Slow Jamz' (performed by Twista featuring Kanye West and Jamie Foxx) | 3:34 | |

| 3. | 'All Falls Down' (featuring Syleena Johnson) |

| 4:05 |

| 4. | 'Two Words' (featuring Mos Def, Freeway and The Harlem Boys Choir) | 4:43 | |

| 5. | 'Jesus Walks' (Church version) | Michael Haussman | 4:04 |

| 6. | 'Jesus Walks' (Chris Milk version) | Milk | 4:06 |

| 7. | 'Jesus Walks' (Street version) |

| 4:18 |

| 8. | 'Jesus Walks' (Making of the video) | 66:56 | |

| 9. | 'The New Workout Plan' (Extended version featuring Fonzworth Bentley) | 8:06 | |

| Total length: | 104:46 | ||

Sample credits[edit]

- 'We Don't Care' contains samples of 'I Just Wanna Stop', written by Ross Vannelli and performed by The Jimmy Castor Bunch.

- 'All Falls Down' contains interpolations of 'Mystery of Iniquity', written and performed by Lauryn Hill.

- 'Spaceship' contains samples of 'Distant Lover', written by Marvin Gaye, Gwen Gordy Fuqua and Sandra Greene, and performed by Marvin Gaye.

- 'Jesus Walks' contains samples of 'Walk with Me', performed by The ARC Choir and '(Don't Worry) If There's a Hell Below, We're All Going to Go', written and performed by Curtis Mayfield.

- 'Never Let Me Down' contains samples of 'Maybe It's the Power of Love', written by Michael Bolton and Bruce Kulick, and performed by Blackjack.

- 'Slow Jamz' contains samples of 'A House Is Not a Home', written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, and performed by Luther Vandross.

- 'School Spirit' contains samples of 'Spirit in the Dark', written and performed by Aretha Franklin.

- 'Two Words' contains samples of 'Peace & Love (Amani Na Mapenzi) – Movement IV (Encounter)', written by Lou Wilson, Ric Wilson and Carlos Wilson, and performed by Mandrill.

- 'Through the Wire' contains samples of 'Through the Fire', written by David Foster, Tom Keane and Cynthia Weil, and performed by Chaka Khan.

- 'Family Business' contains samples of 'Fonky Thang', written by Terry Callier and Charles Stepney, and performed by The Dells.

- 'Last Call' contains samples of 'Mr. Rockefeller', written by Jerry Blatt and Bette Midler, and performed by Bette Midler.

Personnel[edit]

Credits adapted from liner notes.[33][101]

Musicians[edit]

| Production[edit]

Design[edit]

|

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

| Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/Sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (CRIA)[111] | Gold | 80,00 |

| New Zealand (RIANZ)[112] | Gold | 7,500 |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[113] | 2× Platinum | 600,000 |

| United States (RIAA)[114] | 3× Platinum | 3,358,000[115] |

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

References[edit]

- ^ abBarber, Andrew (July 23, 2012). '93. Go-Getters 'Let Em In' (2000)'. Complex. Complex Media. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^Reid, Shaheem (September 30, 2005). 'Music Geek Kanye's Kast of Thousands'. MTV. MTV Networks. Retrieved April 23, 2006.

- ^ abcdMitchum, Rob (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^'500 Greatest Albums of All Time: #464 (The Blueprint)'. Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. November 18, 2003. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ^ abcdefKellman, Andy. 'The College Dropout – Kanye West'. AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ abcdeReid, Shaheem (February 9, 2005). 'Road to the Grammys: The Making Of Kanye West's College Dropout'. MTV. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^Serpick, Evan. Kanye West. Rolling Stone Jann Wenner. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^ abHess, p. 556

- ^ abCalloway, Sway; Reid, Shaheem (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: Kanplicated'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^Williams, Jean A (October 1, 2007). 'Kanye West: The Man, the Music, and the Message.(Biography)'. The Black Collegian. Archived from the original on January 25, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ abcdKearney, Kevin (September 30, 2005). Rapper Kanye West on the cover of Time: Will rap music shed its 'gangster' disguise?Archived February 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^Birchmeier, Jason (2007). 'Kanye West – Biography'. Allmusic. All Media Guide. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ abDavis, Kimberly. 'The Many Faces of Kanye West'Archived January 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (June 2004) Ebony.

- ^Davis, Kimberly. 'Kanye West: Hip Hop's New Big Shot'Archived January 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (April 2005) Ebony.

- ^Kamer, Foster (March 11, 2013). '9. Kanye West, Get Well Soon... (2003) – The 50 Best Rapper Mixtapes'. Complex. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^Reid, Shaheem (December 10, 2002). 'Kanye West Raps Through His Broken Jaw, Lays Beats For Scarface, LudacrisArchived December 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine'. MTV. Accessed October 23, 2007.

- ^Sarad (February 10, 2015). 'Today In Hip Hop History: Kanye West Drops His 'College Dropout' LP 11 Years Ago'. The Source. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^Patel, Joseph (June 5, 2003). 'Producer Kanye West's Debut LP Features Jay-Z, ODB, Mos Def'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^'The College Dropout is EW's Top Album of the Decade'. KanyeUniverseCity. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^'When Rap Lyrics Get Censored, Even on the Explicit Version'. Complex. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^'The Making of Kanye West's 'The College Dropout''. Complex. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^'Kanye West – School Spirit (Uncensored Version)'. Fake Shore Drive®. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^Martins, Jordan (April 19, 2010). 'Tony Williams of G.O.O.D. Music Talks Most Memorable Studio Sessions With Kanye'. Complex. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ abLove, Josh. Review: The College DropoutArchived September 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Stylus Magazine. Retrieved on July 23, 2009.

- ^ abCinquemani, Sal (March 14, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^James, Jim (December 27, 2009). 'Music of the decade'. The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ abcSanneh, Kelefa (February 9, 2004). 'No Reading And Writing, But Rapping Instead'. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^'Kanye West Biography'. Artistdirect. Rogue Digital, LLC. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^UnrecordedArchived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^Sabotage TimesArchived February 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^Burrell, Ian (September 22, 2007). 'Kanye West: King of rap'. The Independent. UK. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^'Hip-Hop Violinist' Preps Solo DebutArchived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Billboard.

- ^ abcdefThe College Dropout (Media notes). Kanye West. Roc-A-Fella Records. 2004.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ abcdefgHeaton, Dave (March 5, 2004). Kanye West: The College DropoutArchived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. PopMatters. Retrieved on August 25, 2011

- ^Hall, Rashaun (January 21, 2005). 'Kanye West Collaborating With Lauryn Hill on New LP'. MTV. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^Jones, Steve (February 10, 2005). 'Kanye West runs away with 'Jesus Walks''. USA Today. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^Mulholland, Garry (August 15, 2004). ''Jesus Walks' by Kanye West'. London: The Observer. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^Calloway, Sway; Reid, Shaheem (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: Kanplicated'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^''Watch The Throne': Jay-Z and Kanye West's 10 Best Collaborations'. Billboard. August 6, 2011. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^Batey, Angus (February 20, 2004). Kanye West – The College Dropout. Yahoo! Music. Retrieved on August 25, 2011

- ^ abReid, Shaheem (January 21, 2004). 'Common, John Mayer Drop in to Preview Kanye West's Dropout'. MTV. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^Ryan, Chris. Review: The College DropoutArchived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Spin. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^Ahmed, Isanul. '15 Things You Didn't Know About Kanye West's 'The College Dropout''. complex.com. Complex. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^Barber, Andrew. 'The 100 Best Kanye West Songs: 24. Kanye West 'Last Call' (2004)'. Complex Music. Complex Media. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^West, Donda, p. 106

- ^Hess, p. 558

- ^Pasori, Cedar; McDonald, Leighton (June 17, 2013). 'The Design Evolution of Kanye West's Album Artwork: The College Dropout'. Complex. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^Goldstein, Hartley (December 5, 2003). 'Kanye West: Get Well Soon / I'm Good'. PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^Ahmed, Insanul (September 21, 2011). 'Kanye West × The Heavy Hitters, Get Well Soon (2003) – Clinton Sparks' 30 Favorite Mixtapes'. Complex. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^Martens, Todd (February 18, 2004). 'More Than A Million Take Norah 'Home''. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Martens, Todd (February 25, 2004). 'Jones Remains At 'Home' At No. 1'. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Martens, Todd (March 3, 2004). 'Norah Makes Comfy 'Home' At No. 1'. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Gold & Platinum: Searchable DatabaseArchived January 7, 2013, at WebCite. Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^Grein, Paul (June 24, 2014). 'USA: Top 20 New Acts Since 2000'. Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^Cibola, Marco (June 14, 2013). 'Kanye West: How the Rapper Grew From 'Dropout' to 'Yeezus''. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^Columnist. Mr Confidence puts it all on the lineArchived October 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Sun-Herald (August 1, 2005). Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ ab'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2014.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^'Does Kanye West's 'The College Dropout' Stand the Test of Time?'. The Boombox. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^'Kanye West's 'The New Workout Plan': Revisit His Hilariously Brilliant 'College Dropout' Single'. Idolator. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^Kanye West's Lost 'Spaceship' Video | Kanye WestArchived June 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Rap Basement Retrieved July 1, 2012

- ^ ab'Reviews for College Dropout by Kanye West'. Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^Pareles, Jon (April 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Blender. New York (25): 124. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ abEndelman, Michael (February 13, 2004). 'The College Dropout'. Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^Baker, Soren (February 12, 2004). 'You'll know his name'. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ ab'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Mojo. London (126): 102. May 2004.

- ^ abCaramanica, Jon (March 14, 2004). 'The College Dropout'. Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^Ryan, Chris (November 2003). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Spin. New York. 19 (11): 111–12. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^Jones, Steve (February 9, 2004). ''Dropout': Well schooled'. USA Today. McLean. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ abChristgau, Robert (March 9, 2004). 'Edges of the Groove'. The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^Rabin, Nathan (February 17, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^'Kanye West, 'The College Dropout' (Roc-A-Fella/Def Jam)'. URB. Los Angeles (114): 111. March 12, 2004.

- ^Hsu, Hua (February 10, 2004). 'The Benz or the Backpack?'. The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^'Kanye West: Album Guide'. Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^White, Julian. 'Rolling Stone 2004 Critics'. RocklistMusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^'Pazz & Jop 2004'. The Village Voice. October 18, 2005. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^Staff. '40 Best Albums of the Year: 1) The College DropoutArchived April 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine'. Spin: 68. January 21, 2005.

- ^'Why You Can't Ignore Kanye'. Time. August 21, 2005. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^Pitchfork staff (February 7, 2005). 'The Top 100 Albums of 2000–04'Archived April 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Pitchfork. p. 6. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^'Time 100 Best Albums of All Time'. Time. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^XXL (December 2007). 'Retrospective: XXL Albums'. XXL Magazine.

- ^The New Classics: MusicArchived February 26, 2012, at WebCiteEntertainment Weekly June 17, 2011 Retrieved on August 13, 2011

- ^10 Best Albums of the DecadeArchived January 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved on January 20, 2010.

- ^Walls, Seth Colter. 'Best Albums – The College Dropout Kanye West (2004)'. Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^Rhapsody Editorial (December 4, 2009). 'Rhapsody's 100 Best Albums of the Decade'. Rhapsody. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^Chennault, Sam (September 31, 2009). 'Hip-Hop's Best Albums of the Decade'. Rhapsody. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^Staff. 100 Best Albums of the Decade: 10) The College DropoutArchived February 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner Retrieved on December 25, 2009.

- ^COS Staff. 'CoS Top of the Decade: The Albums'. Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^Chelsler, Josh. '10 Best Rap Albums of the 2000s'. Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^'The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s'. Fact Mag. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^Drake, David. 25 Rap Albums From the Past Decade That Deserve Classic Status: Kanye West, The College Dropout (2004)Archived December 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Complex, December 6, 2012

- ^The 50 Greatest Debut Albums in Hip-Hop History: 20. Kanye West, The College DropoutArchived January 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Complex, November 27, 2012.

- ^'NEW 500 Greatest Albums: 298. Kanye West, 'The College Dropout''. Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^'THE 100 BEST DEBUT ALBUMS OF ALL TIME – 19: The College Dropout'. Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. March 22, 1963. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (February 7, 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN0-7893-1371-5.

- ^'32nd American Music Awards Nominees'. Billboard. September 14, 2004. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'2004 Billboard Music Awards Finalists'. Billboard. November 30, 2004. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'MOBO Awards 2004 Winners'. MOBO. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Kanye triumphs at Source awards'. BBC. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Kanye triumphs at Source awards'. BBC. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Grammy Awards 2005: Key winners'. BBC. February 14, 2005. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Credits: The College Dropout'. AllMusic. All Media Guide. April 2, 2004. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^'Lescharts.com – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. Hung Medien.

- ^'Offiziellecharts.de – Kanye West – The College Dropout' (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts.

- ^'Swedishcharts.com – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. Hung Medien.

- ^'Official Albums Chart Top 100'. Official Charts Company.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Billboard 200)'. Billboard.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)'. Billboard.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Top Rap Albums)'. Billboard.

- ^'2004 Year-End Charts – Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Albums'. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^'2005 Year-End Charts - Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Albums'. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^'Canadian Recording Industry Association (CRIA): Gold & Platinum – June 2004'Archived November 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Canadian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^Dec'Latest Gold / Platinum Albums'. RadioScope New Zealand. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^'Certified Awards Search'. British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^'Gold & Platinum Searchable Database'[permanent dead link] Kanye West albums. RIAA. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^Grein, Paul (June 24, 2014). 'USA: Top 20 New Acts Since 2000'. Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brown, Jake (2006). Kanye West in the Studio: Beats Down! Money Up! (2000–2006). Colossus Books. ISBN0-9767735-6-2.

- Hess, Mickey (2007). Icons of Hip Hop: an Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN0-313-33904-X.

- West, Donda; Hunter, Karen (2007). Raising Kanye: Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar. Simon & Schuster. ISBN1-4165-4470-4.

External links[edit]

- The College Dropout at Discogs

Kanye West in 2009 | |

| Born | June 8, 1977 (age 42) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Residence | Chicago, Illinois, U.S.[1] Hidden Hills, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | |

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1996–present |

| Home town | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards | List of awards and nominations |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | Hip hop |

| Instruments | |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

| Website | www.kanyewest.com |

Kanye Omari West (/ˈkɑːnjeɪ/; born June 8, 1977) is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, record producer, entrepreneur, and fashion designer. His musical career has been marked by dramatic changes in styles, incorporating an eclectic range of influences including soul, baroque pop, electro, indie rock, synth-pop, industrial, and gospel. Over the course of his career, West has been responsible for cultural movements and progressions within mainstream hip hop and popular music at large.

Born in Atlanta and raised in Chicago, West first became known as a producer for Roc-A-Fella Records in the early 2000s, producing hit singles for recording artists such as Jay-Z, Ludacris and Alicia Keys. Intent on pursuing a solo career as a rapper, West released his debut album The College Dropout in 2004 to widespread critical and commercial success, and founded the record label GOOD Music. He went on to experiment with a variety of musical genres on subsequent acclaimed studio albums, including Late Registration (2005), Graduation (2007), and the polarizing but influential 808s & Heartbreak (2008). He released his fifth album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy in 2010 to further rave reviews, and has since succeeded it with Yeezus (2013), The Life of Pablo (2016) and Ye (2018), as well as full-length collaborations Watch the Throne (2011) and Kids See Ghosts (2018) with Jay-Z and Kid Cudi respectively.

West's outspoken views and life outside of music have received significant media attention. He has been a frequent source of controversy for his conduct at award shows, on social media, and in other public settings, as well as his comments on the music and fashion industries, U.S. politics, and race. His marriage to television personality Kim Kardashian has also been a source of substantial media attention. As a fashion designer, he has collaborated with Nike, Louis Vuitton, and A.P.C. on both clothing and footwear, and have most prominently resulted in the Yeezy collaboration with Adidas beginning in 2013. He is the founder and head of the creative content company DONDA.

West is among the most critically acclaimed musicians of the 21st century and one of the best-selling music artists of all time with over 135 million records sold worldwide.[3] He has won a total of 21 Grammy Awards, making him one of the most awarded artists of all time and the most Grammy-awarded artist of his generation.[4] Three of his albums have been included and ranked on Rolling Stone's 2012 update of the '500 Greatest Albums of All Time' list and he ties with Bob Dylan for having topped the annual Pazz & Jop critic poll the most number of times ever, with four number-one albums each. Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2005 and 2015.

- 2Career

- 4Other ventures

- 5Controversies

- 6Personal life

- 11Tours

- 12Filmography

Early life

Kanye Omari West was born on June 8, 1977, in Atlanta, Georgia.[5][6] After his parents divorced when he was three years old he moved with his mother to Chicago, Illinois.[7][8] His father, Ray West, is a former Black Panther and was one of the first black photojournalists at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Ray West was later a Christian counselor,[8] and in 2006, opened the Good Water Store and Café in Lexington Park, Maryland with startup capital from his son.[9][10] West's mother, Dr. Donda C. (Williams) West,[11] was a professor of English at Clark Atlanta University, and the Chair of the English Department at Chicago State University, before retiring to serve as his manager. West was raised in a middle-class background, attending Polaris High School[12] in suburban Oak Lawn, Illinois, after living in Chicago.[13] At the age of 10, West moved with his mother to Nanjing, China, where she was teaching at Nanjing University as part of an exchange program. According to his mother, West was the only foreigner in his class, but settled in well and quickly picked up the language, although he has since forgotten most of it.[14] When asked about his grades in high school, West replied, 'I got A's and B's. And I'm not even frontin'.'[15]

West demonstrated an affinity for the arts at an early age; he began writing poetry when he was five years old.[16] His mother recalled that she first took notice of West's passion for drawing and music when he was in the third grade.[17] West started rapping in the third grade and began making musical compositions in the seventh grade, eventually selling them to other artists.[18] At age thirteen, West wrote a rap song called 'Green Eggs and Ham' and persuaded his mother to pay for time in a recording studio. Accompanying him to the studio and despite discovering it being 'a little basement studio' where a microphone hung from the ceiling by a wire clothes hanger, West's mother nonetheless supported and encouraged him.[16] West crossed paths with producer/DJ No I.D., with whom he quickly formed a close friendship. No I.D. soon became West's mentor, and it was from him that West learned how to sample and program beats after he received his first sampler at age 15.[19]:557 After graduating from high school, West received a scholarship to attend Chicago's American Academy of Art in 1997 and began taking painting classes, but shortly after transferred to Chicago State University to study English. He soon realized that his busy class schedule was detrimental to his musical work, and at 20 he dropped out of college to pursue his musical dreams.[20] This action greatly displeased his mother, who was also a professor at the university. She later commented, 'It was drummed into my head that college is the ticket to a good life... but some career goals don't require college. For Kanye to make an album called College Dropout it was more about having the guts to embrace who you are, rather than following the path society has carved out for you.'[19]:558

Career

1996–2002: Early work and Roc-A-Fella Records

Kanye West began his early production career in the mid-1990s, creating beats primarily for burgeoning local artists, eventually developing a style that involved speeding up vocal samples from classic soul records. His first official production credits came at the age of nineteen when he produced eight tracks on Down to Earth, the 1996 debut album of a Chicago rapper named Grav.[21] For a time, West acted as a ghost producer for Deric 'D-Dot' Angelettie. Because of his association with D-Dot, West wasn't able to release a solo album, so he formed and became a member and producer of the Go-Getters, a late-1990s Chicago rap group composed of him, GLC, Timmy G, Really Doe, and Arrowstar.[22][23] His group was managed by John 'Monopoly' Johnson, Don Crowley, and Happy Lewis under the management firm Hustle Period. After attending a series of promotional photo shoots and making some radio appearances, The Go-Getters released their first and only studio album World Record Holders in 1999. The album featured other Chicago-based rappers such as Rhymefest, Mikkey Halsted, Miss Criss, and Shayla G. Meanwhile, the production was handled by West, Arrowstar, Boogz, and Brian 'All Day' Miller.[22]

West spent much of the late 1990s producing records for a number of well-known artists and music groups.[24] The third song on Foxy Brown's second studio album Chyna Doll was produced by West. Her second effort subsequently became the very first hip-hop album by a female rapper to debut at the top of the U.S. Billboard 200 chart in its first week of release.[24] West produced three of the tracks on Harlem World's first and only album The Movement alongside Jermaine Dupri and the production duo Trackmasters. His songs featured rappers Nas, Drag-On, and R&B singer Carl Thomas.[24] The ninth track from World Party, the last Goodie Mob album to feature the rap group's four founding members prior to their break-up, was co-produced by West with his manager Deric 'D-Dot' Angelettie.[24] At the close of the millennium, West ended up producing six songs for Tell 'Em Why U Madd, an album that was released by D-Dot under the alias of The Madd Rapper; a fictional character he created for a skit on The Notorious B.I.G.'s second and final studio album Life After Death. West's songs featured guest appearances from rappers such as Ma$e, Raekwon, and Eminem.[24]

West got his big break in the year 2000, when he began to produce for artists on Roc-A-Fella Records. West came to achieve recognition and is often credited with revitalizing Jay-Z's career with his contributions to the rap mogul's influential 2001 album The Blueprint.[25]The Blueprint is consistently ranked among the greatest hip-hop albums, and the critical and financial success of the album generated substantial interest in West as a producer.[26] Serving as an in-house producer for Roc-A-Fella Records, West produced records for other artists from the label, including Beanie Sigel, Freeway, and Cam'ron. He also crafted hit songs for Ludacris, Alicia Keys, and Janet Jackson.[25][27]

Despite his success as a producer, West's true aspiration was to be a rapper. Though he had developed his rapping long before he began producing, it was often a challenge for West to be accepted as a rapper, and he struggled to attain a record deal.[28] Multiple record companies ignored him because he did not portray the 'gangsta image' prominent in mainstream hip hop at the time.[19]:556 After a series of meetings with Capitol Records, West was ultimately denied an artist deal.[18]

According to Capitol Record's A&R, Joe Weinberger, he was approached by West and almost signed a deal with him, but another person in the company convinced Capitol's president not to.[18] Desperate to keep West from defecting to another label, then-label head Damon Dash reluctantly signed West to Roc-A-Fella Records. Jay-Z later admitted that Roc-A-Fella was initially reluctant to support West as a rapper, claiming that many saw him as a producer first and foremost, and that his background contrasted with that of his labelmates.[19]:556[29]

West's breakthrough came a year later on October 23, 2002, when, while driving home from a California recording studio after working late, he fell asleep at the wheel causing a head-on crash with another car.[30] The crash left him with a shattered jaw, which had to be wired shut in reconstructive surgery. The crash broke both legs of the other driver.[31] The accident inspired West; two weeks after being admitted to the hospital, he recorded a song at the Record Plant Studios with his jaw still wired shut.[30] The composition, 'Through The Wire', expressed West's experience after the accident, and helped lay the foundation for his debut album, as according to West 'all the better artists have expressed what they were going through'.[32][33] West added that 'the album was my medicine', as working on the record distracted him from the pain.[34] 'Through The Wire' was first available on West's Get Well Soon...mixtape, released December 2002.[35] At the same time, West announced that he was working on an album called The College Dropout, whose overall theme was to 'make your own decisions. Don't let society tell you, 'This is what you have to do.'[36]

2003–06: The College Dropout and Late Registration

West recorded the remainder of the album in Los Angeles while recovering from the car accident. Once he had completed the album, it was leaked months before its release date.[28] However, West decided to use the opportunity to review the album, and The College Dropout was significantly remixed, remastered, and revised before being released. As a result, certain tracks originally destined for the album were subsequently retracted, among them 'Keep the Receipt' with Ol' Dirty Bastard and 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly' with Consequence.[37] West meticulously refined the production, adding string arrangements, gospel choirs, improved drum programming and new verses.[28] West's perfectionism led The College Dropout to have its release postponed three times from its initial date in August 2003.[38][39]

The College Dropout was eventually issued by Roc-A-Fella in February 2004, shooting to number two on the Billboard 200 as his debut single, 'Through the Wire' peaked at number fifteen on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for five weeks.[40] 'Slow Jamz', his second single featuring Twista and Jamie Foxx, became an even bigger success: it became the three musicians' first number one hit. The College Dropout received near-universal critical acclaim from contemporary music critics, was voted the top album of the year by two major music publications, and has consistently been ranked among the great hip-hop works and debut albums by artists. 'Jesus Walks', the album's fourth single, perhaps exposed West to a wider audience; the song's subject matter concerns faith and Christianity. The song nevertheless reached the top 20 of the Billboard pop charts, despite industry executives' predictions that a song containing such blatant declarations of faith would never make it to radio.[41][42]The College Dropout would eventually be certified triple platinum in the US, and garnered West 10 Grammy nominations, including Album of the Year, and Best Rap Album (which it received).[43] During this period, West also founded GOOD Music, a record label and management company that would go on to house affiliate artists and producers, such as No I.D. and John Legend. At the time, the focal point of West's production style was the use of sped-up vocal samples from soul records.[44] However, partly because of the acclaim of The College Dropout, such sampling had been much copied by others; with that overuse, and also because West felt he had become too dependent on the technique, he decided to find a new sound.[45] During this time, he also produced singles for Brandy, Common, John Legend, and Slum Village.[46]

Beginning his second effort that fall, West would invest two million dollars and take over a year to craft his second album.[47] West was significantly inspired by Roseland NYC Live, a 1998 live album by English trip hop group Portishead, produced with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.[48] Early in his career, the live album had inspired him to incorporate string arrangements into his hip-hop production. Though West had not been able to afford many live instruments around the time of his debut album, the money from his commercial success enabled him to hire a string orchestra for his second album Late Registration.[48] West collaborated with American film score composer Jon Brion, who served as the album's co-executive producer for several tracks.[49] Although Brion had no prior experience in creating hip-hop records, he and West found that they could productively work together after their first afternoon in the studio where they discovered that neither confined his musical knowledge and vision to one specific genre.[50]Late Registration sold over 2.3 million units in the United States alone by the end of 2005 and was considered by industry observers as the only successful major album release of the fall season, which had been plagued by steadily declining CD sales.[51]

While West had encountered controversy a year prior when he stormed out of the American Music Awards of 2004 after losing Best New Artist,[52] his first large-scale controversy came just days following Late Registration's release, during a benefit concert for Hurricane Katrina victims. In September 2005, NBC broadcast A Concert for Hurricane Relief, and West was a featured speaker. When West was presenting alongside actor Mike Myers, he deviated from the prepared script. Myers spoke next and continued to read the script. Once it was West's turn to speak again, he said, 'George Bush doesn't care about black people.'[32][a] West's comment reached much of the United States, leading to mixed reactions; President Bush would later call it one of the most 'disgusting moments' of his presidency.[53] West raised further controversy in January 2006 when he posed on the cover of Rolling Stone wearing a crown of thorns.[32]

2007–09: Graduation, 808s & Heartbreak, and VMAs controversy

Fresh off spending the previous year touring the world with U2 on their Vertigo Tour, West felt inspired to compose anthemic rap songs that could operate more efficiently in large arenas.[54] To this end, West incorporated the synthesizer into his hip-hop production, utilized slower tempos, and experimented with electronic music and influenced by music of the 1980s.[55][56] In addition to U2, West drew musical inspiration from arena rock bands such as The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin in terms of melody and chord progression.[56][57] To make his next effort, the third in a planned tetralogy of education-themed studio albums,[58] more introspective and personal in lyricism, West listened to folk and country singer-songwriters Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash in hopes of developing methods to augment his wordplay and storytelling ability.[48]

West's third studio album, Graduation, garnered major publicity when its release date pitted West in a sales competition against rapper 50 Cent's Curtis.[59] Upon their September 2007 releases, Graduation outsold Curtis by a large margin, debuting at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart and selling 957,000 copies in its first week.[60]Graduation continued the string of critical and commercial successes by West, and the album's lead single, 'Stronger', garnered his third number-one hit.[61] 'Stronger', which samples French house duo Daft Punk, has been accredited to not only encouraging other hip-hop artists to incorporate house and electronica elements into their music, but also for playing a part in the revival of disco and electro-infused music in the late 2000s.[62] Ben Detrick of XXL cited the outcome of the sales competition between 50 Cent's Curtis and West's Graduation as being responsible for altering the direction of hip-hop and paving the way for new rappers who didn't follow the hardcore-gangster mold, writing, 'If there was ever a watershed moment to indicate hip-hop's changing direction, it may have come when 50 Cent competed with Kanye in 2007 to see whose album would claim superior sales.'[63]

West's life took a different direction when his mother, Donda West, died of complications from cosmetic surgery involving abdominoplasty and breast reduction in November 2007.[64] Months later, West and fiancée Alexis Phifer ended their engagement and their long-term intermittent relationship, which had begun in 2002.[65] The events profoundly affected West, who set off for his 2008 Glow in the Dark Tour shortly thereafter.[66] Purportedly because his emotions could not be conveyed through rapping, West decided to sing using the voice audio processor Auto-Tune, which would become a central part of his next effort. West had previously experimented with the technology on his debut album The College Dropout for the background vocals of 'Jesus Walks' and 'Never Let Me Down.' Recorded mostly in Honolulu, Hawaii in three weeks,[67] West announced his fourth album, 808s & Heartbreak, at the 2008 MTV Video Music Awards, where he performed its lead single, 'Love Lockdown'. Music audiences were taken aback by the uncharacteristic production style and the presence of Auto-Tune, which typified the pre-release response to the record.[68]

808s & Heartbreak, which features extensive use of the eponymous Roland TR-808 drum machine and contains themes of love, loneliness, and heartache, was released by Island Def Jam to capitalize on Thanksgiving weekend in November 2008.[69][70] Reviews were positive, though slightly more mixed than his previous efforts. Despite this, the record's singles demonstrated outstanding chart performances. Upon its release, the lead single 'Love Lockdown' debuted at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 and became a 'Hot Shot Debut',[71] while follow-up single 'Heartless' performed similarly and became his second consecutive 'Hot Shot Debut' by debuting at number four on the Billboard Hot 100.[72] While it was criticized prior to release, 808s & Heartbreak had a significant effect on hip-hop music, encouraging other rappers to take more creative risks with their productions.[73]

West's controversial incident the following year at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards was arguably his biggest controversy, and led to widespread outrage throughout the music industry.[74] During the ceremony, West crashed the stage and grabbed the microphone from 'Best Female Video' winner Taylor Swift during her acceptance speech in order to proclaim that, instead, Beyoncé's video for 'Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)', nominated for the same award, was 'one of the greatest videos of all time'. He was subsequently withdrawn from the remainder of the show for his actions. West's Fame Kills tour with Lady Gaga was cancelled in response to the controversy.[75]

2010–12: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and collaborations

Following the highly publicized incident, West took a brief break from music and threw himself into fashion, only to hole up in Hawaii for the next few months writing and recording his next album.[76] Importing his favorite producers and artists to work on and inspire his recording, West kept engineers behind the boards 24 hours a day and slept only in increments. Noah Callahan-Bever, a writer for Complex, was present during the sessions and described the 'communal' atmosphere as thus: 'With the right songs and the right album, he can overcome any and all controversy, and we are here to contribute, challenge, and inspire.'[76] A variety of artists contributed to the project, including close friends Jay-Z, Kid Cudi and Pusha T, as well as off-the-wall collaborations, such as with Justin Vernon of Bon Iver.[77]

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, West's fifth studio album, was released in November 2010 to widespread acclaim from critics, many of whom considered it his best work and said it solidified his comeback.[78] In stark contrast to his previous effort, which featured a minimalist sound, Dark Fantasy adopts a maximalist philosophy and deals with themes of celebrity and excess.[44] The record included the international hit 'All of the Lights', and Billboard hits 'Power', 'Monster', and 'Runaway',[79] the latter of which accompanied a 35-minute film of the same name directed by and starring West.[80] During this time, West initiated the free music program GOOD Fridays through his website, offering a free download of previously unreleased songs each Friday, a portion of which were included on the album. This promotion ran from August 20 – December 17, 2010. Dark Fantasy went on to go platinum in the United States,[81] but its omission as a contender for Album of the Year at the 54th Grammy Awards was viewed as a 'snub' by several media outlets.[82]

2011 saw West embark on a festival tour to commemorate the release of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy performing and headlining numerous festivals including; SWU Music & Arts, Austin City Limits, Oya Festival, Flow Festival, Live Music Festival,The Big Chill, Essence Music Festival, Lollapalooza and Coachella which was described by The Hollywood Reporter as 'one of greatest hip-hop sets of all time',[83] West released the collaborative album Watch the Throne with Jay-Z in August 2011. By employing a sales strategy that released the album digitally weeks before its physical counterpart, Watch the Throne became one of the few major label albums in the Internet age to avoid a leak.[84][85] 'Niggas in Paris' became the record's highest charting single, peaking at number five on the Billboard Hot 100.[79] The co-headlining Watch the Throne Tour kicked off in October 2011 and concluded in June 2012.[86] In 2012, West released the compilation albumCruel Summer, a collection of tracks by artists from West's record label GOOD Music. Cruel Summer produced four singles, two of which charted within the top twenty of the Hot 100: 'Mercy' and 'Clique'.[79] West also directed a film of the same name that premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival in custom pyramid-shaped screening pavilion featuring seven screens.[87]

2013–15: Yeezus and Adidas collaboration

Sessions for West's sixth solo effort begin to take shape in early 2013 in his own personal loft's living room at a Paris hotel.[88] Determined to 'undermine the commercial',[89] he once again brought together close collaborators and attempted to incorporate Chicago drill, dancehall, acid house, and industrial music.[90] Primarily inspired by architecture,[88] West's perfectionist tendencies led him to contact producer Rick Rubin fifteen days shy of its due date to strip down the record's sound in favor of a more minimalist approach.[91] Initial promotion of his sixth album included worldwide video projections of the album's music and live television performances.[92][93]Yeezus, West's sixth album, was released June 18, 2013, to rave reviews from critics.[94] It became his sixth consecutive number one debut, but also marked his lowest solo opening week sales.[95] Def Jam issued 'Black Skinhead' to radio in July 2013 as the album's lead single.[96]

In September 2013, Kanye West announced he would be headlining his first solo tour in five years, to support Yeezus, with fellow American rapper Kendrick Lamar accompanying him as supporting act.[97][98] The tour was met with rave reviews from critics.[99]Rolling Stone described it as 'crazily entertaining, hugely ambitious, emotionally affecting (really!) and, most importantly, totally bonkers.'[99] Writing for Forbes, Zack O'Malley Greenburg praised West for 'taking risks that few pop stars, if any, are willing to take in today's hyper-exposed world of pop,' describing the show as 'overwrought and uncomfortable at times, but [it] excels at challenging norms and provoking thought in a way that just isn't common for mainstream musical acts of late.'[100]

In June 2013, West and television personality Kim Kardashian announced the birth of their first child, North, and their engagement in October to widespread media attention.[101] In November, West stated that he was beginning work on his next studio album, hoping to release it by mid-2014,[102] with production by Rick Rubin and Q-Tip.[103] In December 2013, Adidas announced the beginning of their official apparel collaboration with West, to be premiered the following year.[104] In May 2014, West and Kardashian were married in a private ceremony in Florence, Italy, with a variety of artists and celebrities in attendance.[101] West released a single, 'Only One', featuring Paul McCartney, in December.[105]

'FourFiveSeconds', a single jointly produced with Rihanna and McCartney, was released in January 2015. West also appeared on the Saturday Night Live 40th Anniversary Special, where he premiered a new song entitled 'Wolves', featuring Sia Furler and fellow Chicago rapper, Vic Mensa. In February 2015, West premiered his clothing collaboration with Adidas, entitled Yeezy Season 1, to generally positive reviews. This would include West's Yeezy Boost sneakers.[106] In March 2015, West released the single 'All Day' featuring Theophilus London, Allan Kingdom and Paul McCartney.[107] West performed the song at the 2015 BRIT Awards with a number of US rappers and UK grime MC's including: Skepta, Wiley, Novelist, Fekky, Krept & Konan, Stormzy, Allan Kingdom, Theophilus London and Vic Mensa.[108] He would premiere the second iteration of his clothing line, Yeezy Season 2, in September 2015 at New York Fashion Week.[109]

Having initially announced a new album entitled So Help Me God slated for a 2014 release, in March 2015 West announced that the album would instead be tentatively called SWISH.[110] On May 11, West was awarded an honorary doctorate by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for his contributions to music, fashion, and popular culture, officially making him an honorary DFA.[111][112] The next month, West headlined at the Glastonbury Festival in the UK, despite a petition signed by almost 135,000 people against his appearance.[113] Toward the end of the set, West proclaimed himself: 'the greatest living rock star on the planet.'[114] Media outlets, including social media sites such as Twitter, were divided on his performance.[115][116]NME stated, 'The decision to book West for the slot has proved controversial since its announcement, and the show itself appeared to polarise both Glastonbury goers and those who tuned in to watch on their TVs.'[116] The publication added that 'he's letting his music speak for and prove itself.'[117]The Guardian said that 'his set has a potent ferocity – but there are gaps and stutters, and he cuts a strangely lone figure in front of the vast crowd.'[118] In September 2015, West performed 808s & Heartbreak in its entirety two nights in a row to rave reviews at Hollywood Bowl. The performance featured a 60-person orchestra, a live band, guests from the album and 70 plus dancers.[119] In December 2015, West released a song titled 'Facts'.[120]

2016–17: The Life of Pablo and tour cancellation

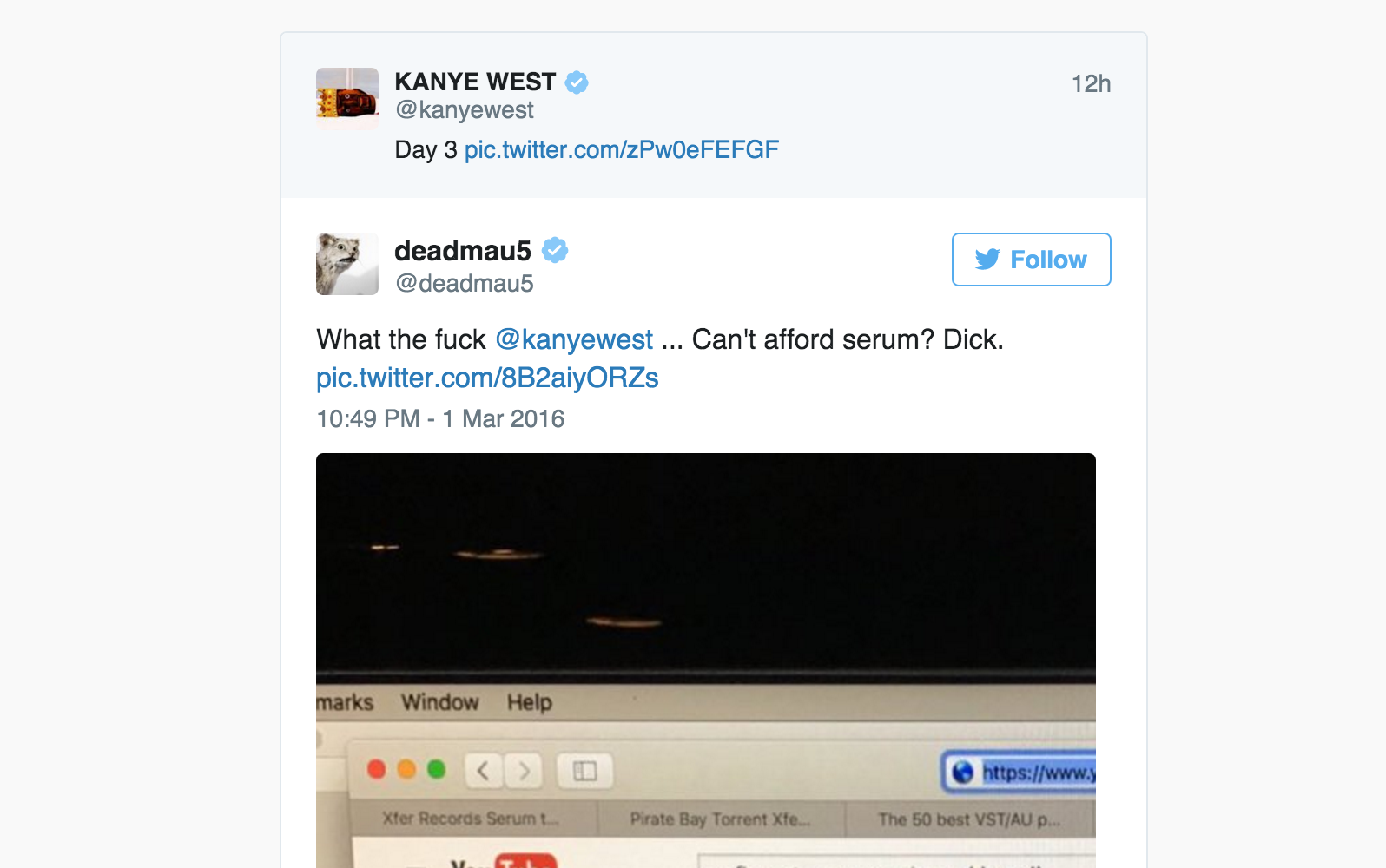

West announced in January 2016 that SWISH would be released on February 11, and later that month, released new songs 'Real Friends' and a snippet of 'No More Parties in LA' with Kendrick Lamar. This also revived the GOOD Fridays initiative in which he releases new singles every Friday. On January 26, 2016, West revealed he had renamed the album from SWISH to Waves, and also announced the premier of his Yeezy Season 3 clothing line at Madison Square Garden.[121] In the weeks leading up to the album's release, West became embroiled in several Twitter controversies[122] and released several changing iterations of the track list for the new album. Several days ahead of its release, West again changed the title, this time to The Life of Pablo.[123] On February 11, West premiered the album at Madison Square Garden as part of the presentation of his Yeezy Season 3 clothing line.[124] Following the preview, West announced that he would be modifying the track list once more before its release to the public,[125] and further delayed its release to finalize the recording of the track 'Waves' at the behest of co-writer Chance the Rapper. He released the album exclusively on Tidal on February 14, 2016, following a performance on SNL.[126][127] Following its official streaming release, West continued to tinker with mixes of several tracks, describing the work as 'a living breathing changing creative expression'[128] and proclaiming the end of the album as a dominant release form.[129] Although a statement by West around The Life of Pablo's initial release indicated that the album would be a permanent exclusive to Tidal, the album was released through several other competing services starting in April.[130]

In February 2016, West stated on Twitter that he was planning to release another album in the summer of 2016, tentatively called Turbo Grafx 16 in reference to the 1990s video game console of the same name.[131][132] In June 2016, West released the collaborative lead single 'Champions' off the GOOD Music album Cruel Winter, which has yet to be released.[133][134] Later that month, West released a controversial video for 'Famous', which depicted wax figures of several celebrities (including West, Kardashian, Taylor Swift, businessman and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, comedian Bill Cosby, and former president George W. Bush) sleeping nude in a shared bed.[135] In August 2016, West embarked on the Saint Pablo Tour in support of The Life of Pablo.[136] The performances featured a mobile stage suspended from the ceiling.[136] West postponed several dates in October following the Paris robbery of several of his wife's effects.[137] On November 21, 2016, West cancelled the remaining 21 dates on the Saint Pablo Tour, following a week of no-shows, curtailed concerts and rants about politics.[138] He was later admitted for psychiatric observation at UCLA Medical Center.[139][140] He stayed hospitalized over the Thanksgiving weekend because of a temporary psychosis stemming from sleep deprivation and extreme dehydration.[141] Following this episode West took an 11 month break from Twitter, and the public in general.[142]

2017–present: Ye, Yandhi, and further collaborations